Chapter 10

10.0 Acid Rock Drainage Communication and Consulting

- 10.1 Introduction

- 10.2 Why Communicate and Consult about Acid Rock Drainage?

- 10.3 Mining Disciplines Involved in Acid Rock Drainage Management and Communication

- 10.4 Planning Communication and Consultation on Acid Rock Drainage

- 10.5 Communication and Consultation about Acid Rock Drainage for each Mining Phase

- 10.6 Good-Practice Principles and Approaches

- 10.7 Responsibilities of Regulators

- 10.8 Guidelines for Acid Rock Drainage Reporting

- 10.9 References

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

10.0 Acid Rock Drainage Communication and Consulting

10.1 Introduction

The purpose of this Chapter 10 is to provide guidance to mining companies in their internal communication, external communication, and consultation with neighbouring communities, regulators, and other stakeholders about ARD during the life of a mine. Key components of this chapter are outlined in Figure 10-1.

This chapter should also be useful to governments, NGOs, and other stakeholders about good practice principles and approaches that may be applicable to communication and consultation initiatives.

Effective communication on ARD cannot be managed in isolation and is only one aspect of the overall mine communication and consultation process. An integrated communication and consultation strategy related to ARD is essential and should reflect key issues to be addressed. While this chapter highlights some specific ARD considerations in communication, the information presented about ARD management is conducted within the broader spectrum of the project or mine consultation processes. The good practice principles and approaches to communication and consultation, and the need for capacity building of stakeholders, apply equally to developed and developing countries. However, the issues, questions, messages, and communication methods are different for each mining phase.

10.2 Why Communicate and Consult about Acid Rock Drainage?

The level of knowledge about ARD generation and mitigation has increased dramatically during the last 20 years within the mining industry, academia, and regulatory agencies. To be fully useful, however, the relevant knowledge applicable to a particular mine or project needs to be translated into a format that can be readily understood by a broad range of stakeholders that could be affected by the project. This consultation should examine the predictions of future drainage quality and the effectiveness of mitigation plans, their degree of uncertainty, and contingency measures to address that uncertainty. Such an open dialogue on what is known, and what can be predicted with varying levels of confidence, helps to build understanding and trust, and ultimately results in a better ARD management plan.

This Section 10.2 presents and discusses stakeholder perceptions and fears about ARD, and the benefits of stakeholder communication and consultation about ARD.

10.2.1 Stakeholder Perceptions about Acid Rock Drainage

Stakeholders generally do not distinguish between ARD, NMD, or SD, nor do they distinguish between mine commodities. Until the stakeholders have a better understanding of the issues, they may express their fears about such things “mine water pollution,” “poor quality water,” “long-term liability,” and “toxic spills.” ARD is different from most other environmental mining issues. If not properly managed, ARD can persist over very long periods of time and may require ongoing study and treatment.

From a stakeholder perspective, regardless of whether the mine is in the developing world or developed world, stakeholders might have some of the following perceptions and views about ARD:

- ARD is perceived as toxic and therefore scary. It turns streams red, kills aquatic life, and renders water unsuitable for domestic purposes. In some countries, such as Papua New Guinea, the red color is culturally associated with a bleeding Mother Earth.

- ARD is perceived as forming somewhat uncontrollably when mining occurs. Also, ARD can migrate into the environment with little warning and therefore risks are harder to explain. This is complicated by the varying levels of understanding and acceptance levels of risk: a lay person’s understanding and perception of risk differs fundamentally from how scientists view risk.

- Some scientific predictions and environmental assessments about ARD have been wrong in the past. The Internet contains examples of ARD from mines having caused significant environmental, social, and economic problems.

- ARD may already have contaminated groundwater and soils, and people question whether the mining company will compensate people for lost resources.

- People doubt the company’s ability to stop ARD, especially where there is a substantial cost and a lack of assurance that it is well managed and controlled.

- Impacts can last from decades to thousands of years unless stopped (claims that are also easily made on the Internet).

Communicating and consulting with stakeholders about issues such as those above is essential to the company’s social license to operate, even if the mine does not have a high risk of ARD. ARD issues should, therefore, be part of the company’s stakeholder communications strategy. Moreover, where ARD is a significant concern, these issues and perceptions pose special challenges, need special measures and skilled people to communicate effectively, and may require the involvement of representatives from all relevant technical disciplines in a company.

It is useful to remember that “trustworthiness goes up when you communicate things that it would be in your self-interest to conceal”.

10.2.2 Benefits of Communication and Consultation about Acid Rock Drainage

Communicating and consulting proactively and transparently about ARD is a necessary and effective way to build good relations with all stakeholders. If communication is done effectively, it contributes to social acceptance of a company’s general business strategy and mining projects and results in better projects and operations, as shown below:

- People fear what they do not understand. Demystifying the concept of ARD by explaining how it forms, how it can be prevented, and how it can be mitigated helps stakeholders overcome concerns and fosters engagement. A good example of general information on ARD/ML developed by the BC Ministry of Energy, Mines & Petroleum Resources for a lay audience can be found here: General Information on Metal Leaching and Acid Rock Drainage

- By providing accurate and timely information, the risk of rumours and the spreading of misinformation and speculation can be reduced. Without accurate information, the media and other stakeholders substitute their own information, which is often based on bad examples of past practice.

- By ensuring that all stakeholders share the same timely accurate information, the community as a whole can develop an informed view on ARD issues.

- Consultation provides balancing of perspectives (IAP2, 2002). By consulting a wide array of stakeholders, a more moderate and pragmatic set of views is generally gained (IFC, 2006a).

- Transparency builds trust and credibility, even if the news is not good.

- Demonstrating to stakeholders, regulators, NGOs, lenders, and others that a company honours its commitments to openness and transparency enables progress.

- Communication represents an opportunity for supporting and building stakeholder capacity to better understand good-practice mining environmental management, and to understand how standards and guidelines are set and used by regulators to evaluate a project.

- Receiving assistance from stakeholders in identifying risks, potential effects, and opportunities to consider can lead to better understanding.

- By listening and engaging, companies are better placed to identify issues at an early stage and deal with issues proactively rather than reactively (Australian Government Department of Industry, Tourism, and Resources, 2007).

- Creating understanding and a supportive environment for decision-making is good business practice.

10.3 Mining Disciplines Involved in Acid Rock Drainage Management and Communication

Ultimately, where ARD is a significant concern, representatives from all mining disciplines, and many mine employees (especially if they live within nearby communities), are involved in communication about ARD. The challenge is, over the life of a mine often with rotating personnel, to instill a lasting culture of constructive internal and external communication.

A mine’s communications department (or public affairs, public relations or community relations department) cannot communicate and consult in isolation. Personnel in these departments may be highly skilled communicators, but they are not normally geochemists, engineers, or mine planners, so the communications department often needs help to explain the complex concept of ARD to stakeholders. The ARD experts and the communications departments need to work closely to understand and effectively convey messages.

10.3.1 Integration of Functions

Many large organizations struggle with internal communication. People in mining companies work in their special disciplines, each representing an important aspect of the business and each with their own responsibility.

Internal communication in a company needs to be designed to be effective between different functional groups at a mine. The functional groups must work together to implement the mine’s ARD management plan (see Chapter 9), including stakeholder engagement, communication and consultation, and performance monitoring. Integration should lead to ARD management and communication being fully incorporated into geological programs, mining, milling, environmental and social management, and communications. At mines where there is a significant risk of ARD, it may be necessary to specifically denote functions and responsibilities pertaining to ARD in the job descriptions of relevant personnel.

Stakeholder engagement needs to be managed as an integral part of company business functions, even if the mining company is small with few staff. The company should provide communications training for personnel and should integrate communications into projects and operations. This increases the chances that ARD communication will serve the purposes of the project, rather than becoming a costly peripheral exercise that is out of touch with operational realities that raises expectations that cannot be met (IFC, 2007). Communication should be driven by a well-defined strategy, and have a clear set of objectives, timetable, budget, and allocation of responsibilities to professional communicators. Many small mining companies subcontract the bulk of communications to consultants, assigning just one staff member as the company spokesperson or liaison.

If there is a significant risk or perception of a risk of ARD, it is advisable to devote a section of the mine’s public consultation and disclosure plan (PCDP) or overall communications plan to ongoing communication about ARD, and build in a mechanism for evaluation of the effectiveness of the ARD communication. It is important to ensure that grievance and compensation procedures are able to specifically deal with ARD. All staff should be made aware of the program and understand why it is being undertaken and what implications it might have for the outcome of the project (IFC, 2007). Personnel in business functions should fully understand the mining process and ARD issues in order to communicate effectively in lay language.

10.4 Planning Communication and Consultation on Acid Rock Drainage

The following basic planning steps, before engaging with stakeholders and communicating and consulting about ARD, are described in this Section 10.4:

- Determine the current state of the mine’s relations with its stakeholders

- Understand the legal and other requirements pertaining to stakeholder engagement regarding ARD

- Ensure that the technical aspects are well understood and accurately and properly prepared for presentation

- Understand the level of knowledge and experience of the stakeholders with ARD

- Tailor the objectives of communication and consultation to the known issues and the situation at hand

10.4.1 The Focus of Consulting and Communication

The focus should always be on conflict prevention, rather than conflict management (Zandvliet, 2007).

The crux of successful communication and consultation is not what you do but how you do it (Zandvliet, 2007). Company-community issues are never due only to external factors. Daily operational activities, more than community projects, determine community perception. Community support is determined by how companies operate, in addition to what they do.

People’s perceptions have to be taken seriously. To them, their perceptions are real, even if factually incorrect. The following examples illustrate this message:

- A company convenes a public meeting (i.e., what the company does is selecting a good communication and consultation methodology), but convenes the meeting badly (i.e., chooses a venue not accessible to stakeholders; creates an “us and them” situation in seating arrangements; discusses technical issues at too high a level; does not allow sufficient time for questions and debate; or becomes defensive and dismissive in answering questions from stakeholders). Thus, how the company conducted the meeting has catastrophic results: open conflict between company and stakeholders, entrenched negative perceptions, and excellent material for negative publicity.

- A company convenes a public meeting that is supposed to be public consultation but presents a single plan with all the conclusions in place to manage ARD; a company has made decisions on what is acceptable risk with respect to ARD and water quality; or a company has decided on a design that requires perpetual treatment without prior discussions with the community.

Thus, consultation and communication about ARD will be influenced by how the company goes about its business, and consequently by whether its stakeholder relationships are good or poor. If relations are poor, communication about ARD will be challenging, and vice versa. Environmental incidents typically serve as a trigger to unleash broader issues that have not been addressed. Even a rumour about ARD can spark a disproportional community reaction when other aspects of the stakeholder relationship have not been dealt with constructively. If the existing risk is already high, and an ARD problem is possible, the risk of losing social license to operate will increase.

Table 10-1 contains a simple assessment tool mines can use to assess current standing in terms of stakeholder engagement (World Bank, 2004). This table is not comprehensive but is illustrative of some of the issues that a mine may face when engagement is not proceeding as planned. These issues vary between geographic regions, ethnic groups, and socioeconomic levels.

| Corporation-Community | Corporation-Government | Corporation-Critics | |

Early indicators |

*Community leaders, elders stating they do not feel respected |

*Government presence in the area of operations is primarily through the military |

*Questions are raised regarding company actions from home government |

Late indicators |

*Rising trends in theft (no reporting and company seen as target) |

*Government encourages communities to demand (and expect) provision of social services from company |

*NGOs encourage community demonstrations against company |

10.4.2 Regulatory and Other Requirements for Communication and Consultation

Before designing a communication and consultation plan, the applicable laws and regulations need to be consulted. The minimum requirements for communication and consultation are often indicated in the applicable mining or environmental laws of the jurisdiction in which the mine operates (see Chapter 3). In some countries, laws other than those for mining and environment could govern communication and consultation. These include access to information (more than 50 countries worldwide now have legislation regarding access to information), administration of public justice, health, and other applicable laws. Bills (i.e., laws) that are not yet promulgated often carry moral force. Complying with in-country regulatory requirements will not bring about social acceptance of a project or stakeholder understanding of an ARD situation. Legislation and regulations usually state the minimum requirements, which will not be adequate if ARD is a significant issue, especially in countries where regulations are not well developed or stakeholders do not trust the government. One way of building trust and credibility at the local level is to assist local stakeholders to understand international guidelines and standards, explain which of their provisions relate to ARD, and show how the mine will apply these to ARD at the local level. The Equator Principles and the IFC Environmental and Social Standards are often useful. For example, the IFC indicators (IFC, 2006b) for free, prior, and informed consultation state that communities should be consulted about impacts that are discovered after operations have started. These impacts would typically include significant changes in the quality of mining discharges, such as impacts related to ARD.

Establish whether there are applicable international conventions. In Europe, for example, the Aarhus Convention on Public Participation (Anon., 1998) indicates that ARD issues that may arise should be disclosed.

Although the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples (ILO, 1989) is directed at governments, companies should study the provisions of this convention for guidance. The provisions of the convention are binding in 17 countries (13 of which are in Latin America). Articles 6 and 15 deal with consultation by government, and companies can assist government with this consultation process.

Local or regional guides on consultation (including “public participation”, “stakeholder engagement”, “community relations”, and “community engagement”) that stakeholders could use to determine whether the company is adequately communicating should also be consulted. Many developed countries have such guidance, bearing in mind those guides are neither recipes nor manuals. In all cases, it is recommended that a company start the process by seeking local and wider stakeholder input into the processes they choose to use.

Company values and commitments often contain requirements for communication and consultation. At a minimum, project and mine site personnel should be keenly familiar with their company’s values and commitments, and should be able to relate these to ARD. Publicly stated values and commitments that are not respected can lead to considerable mistrust between a company and its stakeholders.

10.4.3 Tailor Objectives of Stakeholder Engagement to the Situation at Hand

There is no “one-size-fits-all” approach when it comes to engagement. The type of relationship will differ according to the location, local culture, scale of the project, phase of project development, and the interests of the stakeholders. Figure 10-2 (IFC, 2007) illustrates types of stakeholder engagement and the intensity that people are engaged. A more systematic approach is illustrated in the Spectrum of Public Participation, as shown in Figure 10-3, developed by the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2, 2006a,b,c).

Engagement with stakeholders about an ARD situation under different scenarios is indicated on the figure

The spectrum is a useful tool for mines to select the objectives and nature of stakeholder engagement tailored to their particular situation at various stages during the mining process. Each level of the spectrum has a different objective and a different promise to the public. The terms denoting the different levels are based on dictionary definitions.

The more sensitive the stakeholders the less they trust the company and government, the more impact the stakeholders want on decision-making, and the further to the right on the spectrum they want to be. For example, when a mine operates in a situation of trust between the company, its neighbours, and other stakeholders and an ARD problem arises, communication and consultation would typically occur at the inform and consult levels of the spectrum, taking less time, less involvement of mine personnel, and less cost. On the other hand, a large and potentially far-reaching ARD problem, with potentially significant impacts to people, their water resources and the environment, and especially where there is little trust between the mine and its stakeholders, will be more difficult to manage, will require involvement of all levels of mine personnel, and will cost more time and money.

10.5 Communication and Consultation about Acid Rock Drainage for each Mining Phase

The objectives and nature of communication and consultation about ARD may evolve over the life of the mine. However, consistency in mine personnel and stakeholders involved in consultation helps to build rapport and trust. Companies should be particularly sensitive of the potential effect on relationships during changes in senior mine personnel. Where possible, outgoing senior personnel should introduce the incoming personnel. For example, a mine project leader should involve and introduce the incoming operating mine manager to stakeholders as soon as practical. This inspires confidence in the community that commitments made to manage ARD during the EIS process and permitting will be addressed during mine operations, even as these responsibilities are transferred to different personnel. During the life of the mine, new stakeholders will emerge and, therefore, basic information supplied in the beginning would have to be repeated to assist new stakeholders to understand ARD.

Regardless of the type of mine drainage involved, and the particular commodity, the approaches to and guidelines for communication and consultation are the same and globally applicable, whether in the developing or developed world. Education levels vary among stakeholders in all countries and cultural considerations are important in all societies. Only the stakeholders and issues are different. Processes depend on local circumstance, stakeholders, level of education/literacy, cultural imperatives, current level of trust in and relationship with the mining company, and the nature and severity of problems and impacts. Thus, there is no easy formula, except to try to manage the process proactively and adapt the established good practice approaches and principles for stakeholder engagement (IFC, 2007) and tailor the processes to each situation. A few important good practice approaches and principles are presented in the Section 10.6 (modified from IFC, 1998; IFC, 2007; Chamber of Mines of South Africa, 2002; and IAP2, 2006a,b,c).

Table 10-2 contains a list of sources with more in-depth information.

10.6 Good-Practice Principles and Approaches

10.6.1 Inclusive Engagement

A solid foundation of the stakeholder consultation program is based on recognizing the broad range of potentially interested parties, and the influence of the parties on the project outcomes. Stakeholders within a sector or a community do not form a homogenous group, and include people with different aspirations, values, and challenges. There may be cultural and tribal influences that influence how stakeholders and their influence are defined. So, for example, special efforts have to be made in patriarchal mining communities to engage with women. Women’s ability to participate in the engagement process may be limited for many reasons and it is the responsibility of the company to identify such groups and seek their input, otherwise the consultation will be incomplete.

| Title | Description |

| ICMM’s Community Development Tool-kit | Provides various tools from assessment to monitoring. Includes such items as stakeholder identification, community mapping, partnership assessment, and indicator development. |

| Stakeholder Engagement. A good-practice handbook for companies doing business in emerging markets (IFC, 2007) | This is a most useful tool for mining companies. Part One contains the key concepts and principles of stakeholder engagement, the practices that are known to work, and the tools to support effective delivery. Part Two shows how these principles, practices, and tools fit with the different phases of the project cycle, from initial concept through construction and operations, to divestment and/or decommissioning. Each of these phases presents different risks and opportunities and thus different practices need to be employed and integrated into management systems at each stage. |

| Working with indigenous communities (Australian Government Department of Industry, Tourism and Resource, 2007) | Companies that are signatories to the Minerals Council of Australia’s Enduring Value framework (MCA, 2005), based on the International Council on Mining and Metals’ Sustainable Development Principles (ICMM, 2003), undertake to ‘engage with and respond to stakeholders through open consultation processes’ integral to each stage of a mining operation, from design and construction, through to operation and closure. The handbook provides guidance on how to translate these higher level policy commitments into improved practices on the ground. It focuses on the challenges that companies may encounter as they engage with indigenous communities. Companies need to develop trusting and mutually respectful relationships with local communities. The handbook contains practical examples on how to implement good practice at the site level. |

| Best Practices in Community Involvement (NOAMI, 2003) | In 2002, case studies related to community involvement were completed for three Canadian mine sites, along with experiences in community involvement at abandoned mines in the United States. The “lessons learned” from these studies were developed into principles for use by governments, industry, local communities and other parties as a template for the development of policy and citizen engagement plans prior to, during and after the rehabilitation of problematic sites. The final report and the pamphlet are available on the NOAMI website. |

| The Practitioner’s Handbook on Stakeholder Engagement. (Account Ability, United Nations Environment Programme, Stakeholder Research Associates Canada Inc. 2005). | This handbook is the result of UNEP’s interest to in producing a best practice guide to stakeholder engagement. It provides practical guidance, advice, methodologies, and signposts for further information to those interested in how to make stakeholder engagement more effective and beneficial for the organizations and stakeholders. |

| Ask First: A guide to respecting Indigenous heritage places and values (Australian Heritage Commission, 2002) | The main part of this guide is the consultation and negotiation process with indigenous peoples. It contains good-practice principles and useful guidelines for identification of traditional owners, other indigenous people and nonindigenous stakeholders. |

| The IAP2 Public Participation Toolbox (International Association for Public Participation) (IAP2a,b,c) | This useful toolbox contains a comprehensive listing of public participation techniques and the strong and weak points of each. |

Typical questions to ask when developing a stakeholder contact list are as follows (modified from IFC, 1998; IFC, 2007):

- Do local laws or international initiatives the mine has committed to, specify which stakeholders to consult?

- Who would be directly or indirectly affected? (ARD has the potential to cause effects well downstream of the mine.)

- Who may perceive themselves to be adversely impacted (even if they are not) or who considers themselves the representatives of impacted people?

- What are the various interests of project stakeholders, even if not affected, and what effects might this have on the project?

- Which stakeholders work in or with the affected communities? These could include local government officials, community leaders, NGOs and other civil society organizations. While these groups may not be affected by the project, they may be able to influence the relationship of the mine with affected communities. They could also play a role in identifying risks, potential impacts, and opportunities. NGOs, particularly those who represent communities directly affected by a project, can be important sources of local knowledge, sounding boards for project design and mitigation, and conduits for consulting with sensitive groups. NGOs can also act as partners in planning, and assist implementing and monitoring various project-related programs.

- Which stakeholders might help to enhance the project design or reduce project costs?

- Who strongly supports or opposes the changes that the project will bring and why? The most vocal opposition to a project may come from stakeholders outside the affected area - in other parts of the country, or from other countries. If there is NGO opposition, engaging them early to try and understand their critiques offers an opportunity to manage these issues before they escalate or find another outlet for expression.

- Whose opposition could be detrimental to the success of the project? For example, if negatively influenced by other stakeholders without the benefit of balancing perspectives, the opposition of government, politicians and lenders, would be detrimental.

- Which stakeholder organizations might the mine wish to partner with in the implementation of community development projects? These may include NGOs, government bodies, multilateral organizations, donors, and religious groups.

- Which groups may be interested but may find it difficult to participate? Such groups could include women, the youth, and old and vulnerable people.

Remain sensitive to changes in society, especially when the mine may be operating for two or more decades. Therefore, be flexible in communications planning. Leadership may change; new politicians may become prominent; new organizations may become established; key people may move away and values may change.

10.6.2 Get in Early

Don’t wait until there is a problem to engage. Engaging with stakeholders from the start – as part of the mine’s core business strategy – enables a proactive cultivation of relationships that can serve as “capital” during challenging times. Reaching out to third parties, such as local government officials or NGOs, for assistance as allies or intermediaries only after a problem occurs may be more difficult because of perceived reputational risks of being associated with the company (IFC, 2007). In regard to ARD, especially if there is a high risk of ARD developing, early communication should include what ARD is, how it forms, and how the mine intends to manage the risk.

10.6.3 Be Respectful to People and Cultural Norms

Every society is different. Stakeholder values might differ from the values of company personnel, particularly when the company personnel come from different parts of a country or of the world. This can lead to mine personnel being seen as ‘outsiders’ or ‘intruders,’ or at best as a surrogate government that can deliver benefits. Become a good neighbour by showing respect to people and their values. Ensure that contractors do the same.

Include local cultural norms and basic customary greetings in the local language in induction training. Publicly and with respect, recognize local leadership, and involve local leadership in communicating with the community. Use communication personnel that speak local languages and understand local culture and customs.

The special values, and how they are expressed, for local water bodies, sacred sites, and resources by the community may appear strange to company personnel, but such values are often important elements of a local culture. While these sentiments might not be fully understood, they need to be appreciated and addressed in the ARD management plan. Mutual capacity building of the local community members in technical mining and environmental issues, including ARD and of the mining company personnel and consultants in local cultural aspects, is required and a key step in building communication and ultimately trust.

10.6.4 Accessible and Transparent Information

Consultation at all levels will be more constructive if regulators, affected communities, and other stakeholders have accurate and timely information about aspects that may have impact on them (IFC, 2007).

It is important that governments and companies in the extractive industries recognize transparency and the need to enhance public financial management and accountability. It is also important to achieve this transparency in the context of respect for contracts and laws (Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, 2005, Principles 5 and 6).

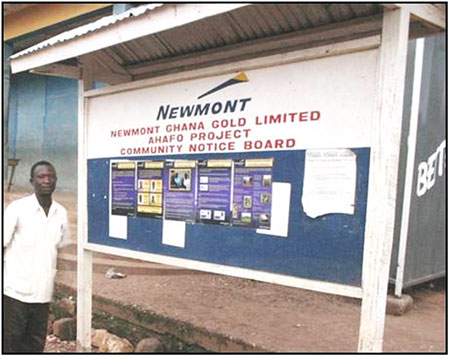

The benefits of using visual materials during communication and consultation (e.g., before and after photographs from other mines, photographs of monitoring and testing by scientists, line drawings and simple graphics) throughout the mine life cannot be overemphasized. (Figure 10-4).

ARD monitoring results can be displayed in this way, and constantly updated to show progress

The crux of making information accessible to a wide range of people is to have a good mix of written, visual, and verbal information. Materials should be available in local languages and complex concepts. For example, ARD should be explained in simple lay person’s language. When explaining complicated concepts to lay people, use the words that will be understood and not the words you would use when talking to a colleague.

Complex technical documents, such as environmental and social impact reports, should be summarized, simplified, and translated, and also visually displayed. Before and after photographs from elsewhere in the world illustrating how rehabilitation, including cleanup of ARD, was done, are very useful in assisting stakeholders to comprehend that impacts can be mitigated. Many mine communities do not have access to the Internet and some communities do not have telephone or postal services. Therefore, materials should also be available as hard copies. Local methods of disseminating information within stakeholder groups should be used. Site visits are also a good method of increasing understanding and information dissemination.

10.6.5 Ongoing Feedback and Acknowledgment

The number of people that attended meetings is not an indication of a successful consultation process. Success depends on how stakeholders experienced the process. Typical questions to ask include:

- Was the information we provided easy for you to understand?

- Did you find the information useful?

- Did you learn something new?

- Did you get the impression that we valued your inputs?

- Did you receive sufficient feedback?

- Do you feel that we have honoured the commitments that we made?

For each question, add a “why.” Responses will provide the mine with direction on how to improve its process.

In addition, the Social and Environmental Assessment and Management Systems Standard of the IFC Performance Standards on Social and Environmental Sustainability (IFC, 2006b) contains a component on ‘community engagement’, together with a number of indicators for ascertaining free, prior and informed consultation which could be used in the evaluation.

Keep thorough records of meetings held, who attended, what was discussed, undertakings given, materials distributed, and grievances received and dealt with. It is important to record the results of consultation, consolidate the issues, questions, and views of all stakeholders into a comments/issues and response report. It is a good idea to categorize this report into groups of issues and, where ARD is an issue, dedicate a category specifically to ARD. Also, conduct an evaluation from time to time of how stakeholders experienced the consultation process pertaining to ARD. This evaluation can be done in a number of formal or informal ways. What is important is that the evaluation should be outcome-based. Include these data into any reporting done. If the results of the evaluation were not good, do not hide it, but list points for improvement and commit to deal with the poor results.

People want to feel like they are being heard; if people feel like they are not being acknowledged, they lose interest or start mistrusting the process. Consulting people entails an implicit “promise” that, at a minimum, their views will be considered during the decision-making process. It also means taking feedback received during the consultation process seriously and making best efforts to address issues raised through changes (e.g., to project design or proposed mitigation measures). In the case of an ARD issue arising and a process being launched to evaluate different options of resolving the problem, stakeholders want to know what happened to their suggestions, they require feedback on the option selected and ongoing feedback of monitoring results. Feedback can be provided in various written, visual, and verbal ways.

10.6.6 Dispute Management and Resolution

Ideally, methods of addressing disagreements and disputes should be in place from the early stages of the project (usually the beginning of the social and environmental assessment process for the proposed mine). Addressing disagreements and dispute should be done throughout construction and operations to the end of project life. Processes might be established by government laws, regulations, permits, or established by the company and in cases of some informal processes might be established by the local community. Mechanisms of resolving disagreements and disputes should be known by all stakeholders. Such mechanisms should be applicable to addressing issues that may arise related to ARD.

As with the broader process of stakeholder engagement, mine and project management should stay informed and involved in issues as they develop so that decisive action can be taken when needed to avoid escalation of disputes. IFC (2007) lists points worth considering when setting up a mechanism for addressing disputes and disagreements.

10.6.7 The Principles of Risk Communication

When mine personnel communicate about ARD, the communicating is about risk. More than three decades of research and hundreds of articles published in scientific journals underpin the science of risk communication (Covello, 1998). Sandman (1986) states that “The most common sources of risk information are people who are professionally inclined to ignore feelings. And how do people respond when their feelings are ignored? They escalate — yell louder, cry harder, listen less — which in turn stiffens the experts, which further provokes the audience. The inevitable result is the classic drama of stereotypes in conflict: the cold scientist or bureaucrat versus the hysterical citizen.”

Mine personnel that have contact with stakeholders and neighbours can reduce the mine’s social risk by becoming familiar with and applying the basic principles of risk communication. Some ways of reducing social risk are listed below:

- Understand that the risks that could kill people and the risks that upset people are often completely different (Covello, 1998).

- Do not use the Decide, Announce, Defend (DAD) Model: Leave room for dialogue and resolving disputes before decisions are implemented (Covello, 1998).

- Express caring, empathy and commitment, respond humanely, and show respect. Do not trivialize people’s feelings. These attributes account for over 50 percent of trust in high-concern situations. When people are worried and upset, they don’t care what you know until they know that you care. People often decide if a person is caring within 9 seconds (Covello, 1998).

- Adapt to the fact that some people might use health, safety, and environmental risks as a proxy or surrogate for other social, political, or economic concerns (Covello, 1998). Assist them to express their unspoken but real concerns. For example, nearby neighbours may claim compensation for ARD-polluted water, but their real concern may be that a nearby community received more “benefits” from the mine than they did. To enter into an endless argument about whether or not the water is polluted will be futile. Personally and patiently explaining the criteria for distribution of benefits may resolve the issue.

- Do not use complex technical language to communicate information about risks. (Covello, 1998). Keep the language appropriate to the audience and the topic of discussion.

- Coordinate and collaborate with other credible sources (USEPA, 1988). If ARD is perceived to be a risk or hazard by stakeholders, enable and support the stakeholders to compare water quality variables to international standards and guidelines. Indicate which international bodies have research or other programs in place and also indicate that the company will work with those to ensure the latest technology and best practice is brought to bear on the problem.

- Avoid negative public relations techniques such as stonewalling, smoke-screening, whitewashing, and blaming someone else (Susskind and Field, 1996).

- Let go of some control. Allow stakeholders to select the dates and times of meetings, to indicate the language of their choice, to indicate by what methods they would like to receive their information, to assist in listing criteria for making choices, and to assist in exploring alternatives (Greyling, 1999). Lay people “undeterred by conventional expert wisdom, often have good ideas that experts can adapt to the situation at hand; at a minimum, lay people are the experts on what frightens them and what would reassure them” (Sandman, 1986).

10.7 Responsibilities of Regulators

In some countries, regulators have the responsibility for conducting consultation before making decisions such as granting exploration permits, environmental permits, or approving an ARD rehabilitation plan or an ARD management plan.

In many countries’ laws, this responsibility includes regulators placing an advertisement in a local newspaper and convening a public hearing (or public meeting). If no or little communication and consultation preceded this, and no relationship exists between the mining company and its stakeholders, such a public gathering could be catastrophic. This would place the regulator in a difficult position to authorize a permit for an activity, even if the activity had technical and economic merit and was environmentally acceptable.

Mine companies are, therefore, advised to share responsibilities with government for disclosure and consultation (IFC, 2007). Below are examples of recommended approaches:

- Assign a dedicated member of personnel (usually the environmental manager) to identify the appropriate contact person (or persons) and an alternate for each relevant regulator at all spheres of government with whom to establish a relationship. Meet with the contact person regularly, both formally and informally.

- In regard to ARD, bear in mind that while government officials may have tertiary qualifications, these qualifications may be in disciplines totally different from geochemistry, water quality, or mine design. Make special efforts to explain ARD in simpler terms and support their capacity building. More general information on metal leaching and ARD, such as that produced by the BC Ministry of Energy Mines and Petroleum Resources (2006), might be helpful.

- Take regulators to on-site visits to the mine and processing plant, and assist them to fully understand the mining process and activities that could cause ARD.

- At times, bring different regulators together to assist in coordination.

- Keep regulators fully informed of communication and consultation initiatives by the mining company and ensure that regulators receive all materials intended for external audiences, including materials related to ARD. If important meetings are to be held with stakeholders, invite regulators in advance and, if necessary, schedule the meetings for a time and date that suits regulators.

- If regulators have responsibility for convening public hearings, offer to assist to convene and record the meeting, offer to develop relevant materials and visual displays, and offer to distribute materials in advance. Ensure, however, that the regulator is still the convenor. Communicate also to the regulator that the mine would be conducting its own consultation process in advance.

- Assist regulators by consolidating the issues, questions, and views of stakeholders into a single report, with responses to each issue (commonly referred to as a comments/issues and response report) issues log, or issues tracking register. Such a consolidated record will portray a wide range of views and will demonstrate that the views of extreme critics are not representative of the larger majority (IFC, 2006a).

In some countries, government may discourage public involvement in decisions. This discouragement places the mining company and NGOs in a difficult position. An innovative solution may be needed for such scenarios that respects government needs but still provides some information and opportunity for consultation with stakeholders. Building capacity of government officials regarding the trust and respect they will gain from consulting with stakeholders is beneficial and leads to better decisions without undermining a government official’s mandate.

10.8 Guidelines for Acid Rock Drainage Reporting

It is important to have transparent and accurate internal and external reporting by mining companies (and this should include reporting on ARD) because transparent reporting contributes to improved practice, may be a requirement by lenders or regulatory authorities, and, more broadly, builds credibility with stakeholders.

Aspects that might be addressed in the ARD report are as follows:

- The risk (likelihood and consequence) of ARD from mine components such as waste facilities, mine workings and stockpiles, typically based on the inherent ARD characteristics of the materials mined and managed

- Results of monitoring before construction and operation, compared to results of monitoring during construction and operation and to regional or country requirements or international guidelines relevant to the project (Reporting on the results of monitoring by external, independent monitors is particularly useful for establishing credibility.)

- Any significant commitments made to regulators and stakeholders and progress with these commitments (In particular, publicize any material changes to commitments or implementation actions that vary from publicly disclosed documents. [IFC, 2007])

- Any significant ARD issues that arise during operations, steps to address the issue, steps to rehabilitate any contamination, disclosure of the situation and consultation with stakeholders, and any modifications required to the mine’s closure plan as a result

- After closure, reporting on implementation of the mine’s closure plan, including success in mitigating ARD and monitoring results over time

ARD issues, management plans, and performance could be integrated into overall corporate or specific mine site health safety environment and community (HSEC) plan or sustainability reports (see, for example, Placer Dome, 2005). ARD management is usually only one of several environmental issues a company or site is addressing, and stakeholders appreciate a full analysis and accounting of environmental performance.

All the mine’s stakeholders, including regulators, local communities, project-affected people, the media, and the mine’s shareholders should be included in the reporting process. Reporting by text in fairly simple language, with ample use of photographs, is more effective than merely presenting performance tables.

More frequent reporting may be required where a significant ARD issue has arisen. This could be done in a number of ways: at meetings with stakeholders, at an annual environmental report-back meeting and site visit, at meetings of the mine’s monitoring forum (if this has been established), in written materials, and in the media. Earley and Staub (2006) report that at a Santa Cruz mine site an extensive database of monitoring results was compiled. Various publications, including memos and brochures, were produced for internal and external communication among the workers at the sites; by state, local, and federal government representatives; by regulators and by the public. Such materials could also be placed on community notice boards.

10.9 References

- Account_Ability, United Nations Environment Programme, Stakeholder Research Associates Canada Inc., 2005. The Practitioner’s Handbook on Stakeholder Engagement.

- http://www.accountability.org.uk

- http://www.StakeholderResearch.com

- http://www.uneptie.org

- Anon., 1998. Aarhus Convention on Public Participation. http://www.unece.org/env/pp/welcome.html

- Australian Heritage Commission, 2002. Ask First: A guide to respecting Indigenous heritage places and values.

- http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/ahc/publications/commission/books/ask-first.html

- British Columbia (BC) Ministry of Mines and Petroleum Resources, 2006. General Information and Metal Leaching and Acid Rock Drainage. http://www.em.gov.bc.ca

- Chamber of Mines of South Africa, 2002. Public participation guidelines for stakeholders in the mining industry, First Edition. Consultative Forum on Mining and the Environment, Chamber of Mines of South Africa, Marshalltown, South Africa. http://www.bullion.org.za

- Covello, V. T., 1998. Risk and Trust in Communications. International Council on Metals and the Environment (ICME) Newsletter, Centre for Risk Communications, New York, NY.

- Earley III, D., and M.W. Staub, 2006. Sustainable Mining Best Practices and Certification. In: R.I. Barnhisel (Ed.), Poster paper 7th International Conference on Acid Rock Drainage (ICARD), March 26-30, St. Louis, MO, American Society of Mining and Reclamation (ASMR), Lexington, KY.

- Equator Principles, http://www.equator-principles.com

- Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, 2005. http://eitransparency.org

- Greyling, T., 1999. Towards environmental dispute resolution: appropriate public participation. In: Proceedings of a Conference on Environmental Dispute Resolution, June, Fourways, South Africa.

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), 2002. Public Participation – critical for sustainable development. IAP2 submission to the World Summit on Sustainable Development. http://www.iap2.org

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2a), 2006a. Spectrum of Public Participation. http://www.iap2.org

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), 2006b. Planning for Effective Public Participation. IAP2 Certificate Training Course Module 1.

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2), 2006c. IAP2 Public Participation Toolbox. http://www.iap2.org

- International Council on Mining & Metals (ICMM), 2003. Sustainable Development Principals. http://www.icmm.com/our-work/sustainable-development-framework/10-principles

- International Finance Corporation (IFC), 1998. Good Practice Manual, Doing Better Business through Effective Public Consultation and Disclosure.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC), 2006a. The BTC Pipeline Project: Lessons of Experience.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC), 2006b. Performance Standards on Social and Environmental Sustainability. http://www.ifc.org/enviro

- International Finance Corporation (IFC), 2007. Stakeholder Engagement. A good practice handbook for companies doing business in emerging markets. http://www.ifc.org

- International Labour Organization (ILO), 1989. ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. http://www.ilo.org

- Australian Government Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources, 2007. Working with Indigenous Communities. Leading Practice Sustainable Development Program, DITR, Canberra. http://www.ret.gov.au/sdmining

- Minerals Council of Australia (MCA), 2005. Enduring Value: The Australian Minerals Industry Framework for Sustainable Development. http://www.minerals.org.au

- National Orphaned/Abandoned Mines Initiative (NOAMI), 2003. Best Practices in Community Involvement: Planning For and Rehabilitating Abandoned and Orphaned Mines in Canada. http://www.abandoned-mines.org

- Placer Dome, 2005. Sustainability report. Canadian Operations, Placer Dome, Toronto, ON.

- Sandman, P.M., 1986. Explaining Environmental Risk: Dealing with the public. TSCA Assistance Office, Office of Toxic Substances, U.S. EPA, November, 14-25.

- Susskind, L. and P. Field, 1996. Dealing with an Angry Public - The Mutual Gains Approach to Resolving Disputes. MIT Harvard.

- World Bank, 2004. Social Development Notes. Conflict prevention and reconstruction. Redefining corporate social risk mitigation strategies. No. 16.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), 1988. Seven Cardinal Rules of Risk Communication. Pamphlet drafted by Vincent T. Covello and Frederick H. Allen, OPA-87-020, April, Washington, DC.

- Zandvliet, L., 2007. CDA Collaborative Learning Projects.

List of Tables

- Table 10-1: Assessment Tool: Indicators of Negative Engagement with Stakeholders

- Table 10-2: Sources with More Information on Principles, Approaches, and Techniques for Communication and Consultation with Stakeholders

List of Figures

- Figure 10-1: Chapter 10 Layout/Road Map

- Figure 10-2: Types of stakeholder engagement and the intensity with which people are engaged (IFC, 2007). Engagement with stakeholders about an ARD situation under different scenarios is indicated on the figure

- Figure 10-3: IAP2’s Public Participation Spectrum

- Figure 10-4: A notice board in a mining community in Ghana where materials are on permanent display. ARD monitoring results can be displayed in this way, and constantly updated to show progress